DU Astronomers Unveil Key Carbon Dust Discoveries

New discoveries from DU researchers reveal how massive stars can shape the building blocks for planet formation.

Researchers who presented newsworthy results at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in National Harbor, Maryland pose for a photo after their press conference. DU doctoral student Emma Lieb (middle) presented her work on the dust-producing binary system WR140.

University of Denver astronomers have revealed new insights into how carbon-rich dust—which is crucial for planet formation—forms and expands in space.

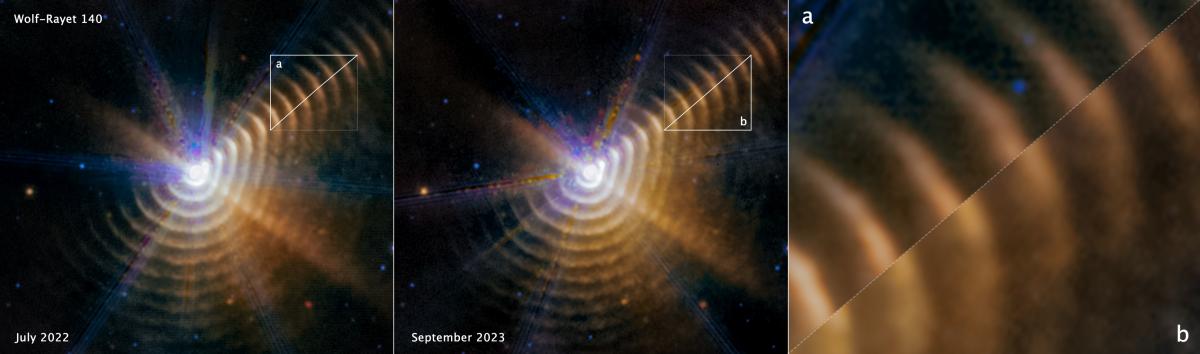

Led by doctoral student Emma Lieb, the research team used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to study WR140 using a time-lapse of images taken in July 2022 and September 2023.

This two-star system, which is seen as a meaningful contributor to the “dust budget” of our galaxy, includes two stars which orbit around each other once every eight years and, as the two massive stars move past each other, their stellar winds collide and create dust. The dust then expands outward and forms a pattern of regularly spaced shells surrounding the stars.

The dust budget, as Lieb describes it, is the number one factor to consider when determining how many planets are formed in a galaxy. Doing this type of work helps researchers better determine how much carbon-rich material there is in the galaxy and, therefore, where and when can planets be formed from that material, she says.

Lieb says the three major takeaways from the research are:

1. The dust shells are moving away from the stars incredibly quickly— at more than 1,600 miles per second or almost 1% the speed of light.

2. The dust shells are not perfectly uniform and are instead clumpy or bumpy. These larger instabilities provide a “fingerprint” that tells researchers like Lieb something about the physical mechanism for the dust’s creation.

3. This star system will enrich the interstellar material with its carbon-rich dust at some point, and this tells us that massive binary stars like WR140 might be an important and underappreciated source of dust in the Milky Way.

The two mid-infrared images of WR140 are shown. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

The results were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on Jan. 13 and were presented this week at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in National Harbor, Maryland.

Several researchers were involved in this work, including DU professor and astronomer Jennifer Hoffman—who also serves as Lieb’s doctoral advisor.

Researchers are now able to study the fine details of this dust formation on short timescales, thanks to the telescope’s unprecedented capabilities.

“We're starting to have the capability to measure these very short time scales of what's going on around us in our neighborhood of the universe,” Hoffman says. “It makes it feel like we’re in a much more dynamic cosmic neighborhood than we have appreciated in the past.”

The dust creation is not only happening on a very relatable, human timescale, its expansion can also be seen over only the course of a year.

“It’s not this abstract idea of where is this dust, when is this dust being formed, when is the next shell being formed? It’s being formed right now and in several more years, we’ll be able to take another picture (and see more growth),” Lieb says.

The telescope’s mid-infrared images show that dust formation has occurred for at least 130 years, and researchers believe the process will continue––generating tens of thousands of dust shells over hundreds of thousands of years.

“(The James Webb Telescope) has completely changed not just our ability to look further and further into space, but at a higher resolution than we’ve ever seen before and also at a somewhat new wavelength,” Lieb says. “We’ve had infrared telescopes in the past … (but with JWST) we’re able to look further and further into the galaxy and into our universe.”