From Catching to Calling in Creativity

Author(s)

Erin K. Anderson-Camenzind, PhD

4D Director of Faculty Innovation and Professor of Communication Studies

erin.willer@du.edu

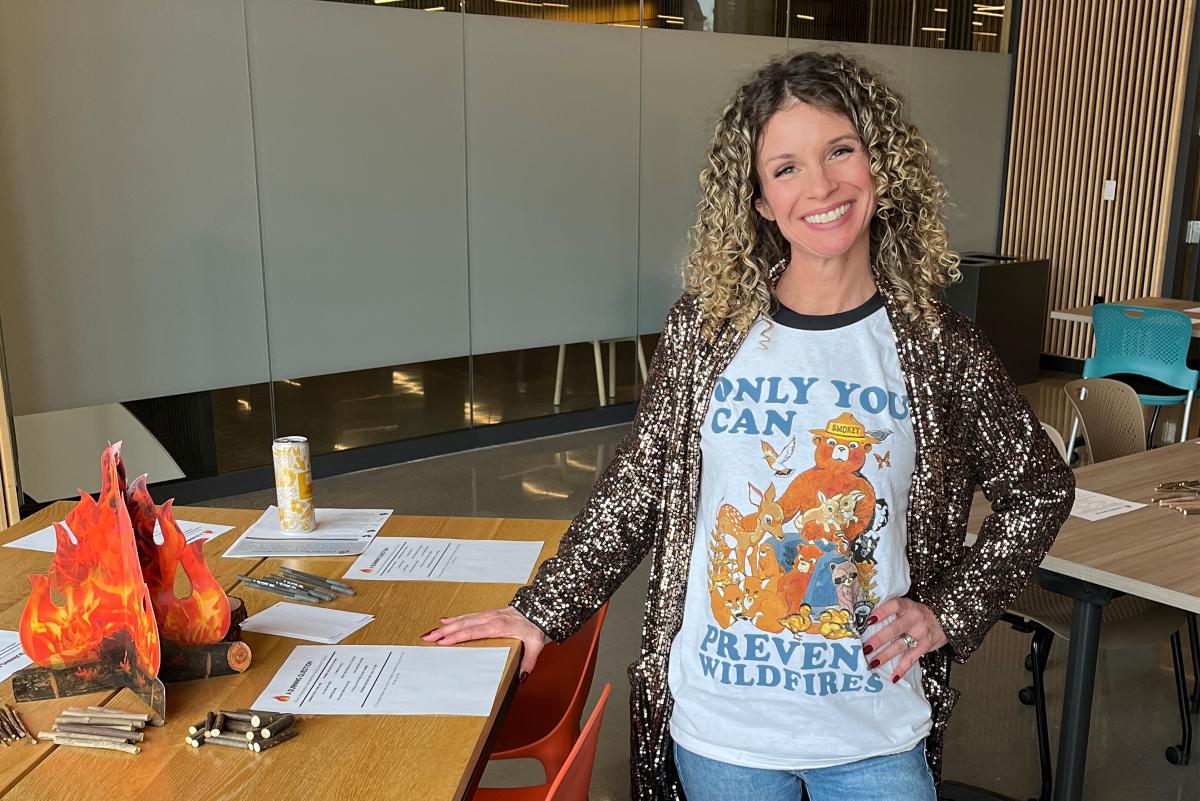

Erin practicing creativity by wearing an outfit matching a workshop she was leading on faculty burnout.

Views and statements from the author do not necessarily reflect official positions of the University of Denver.

“If you have an idea you’re excited about and you don’t bring it to life, it’s not uncommon for the idea to find its voice through another maker. This isn’t because the other artist stole your idea, but because the idea’s time has come.

“In this great unfolding, ideas and thoughts, themes and songs and other works of art exist in the aether and ripen on schedule, ready to find expression in the physical world.

“As artists, it is our job to draw down this information, transmute it, and share it. We are all translators for messages the universe is broadcasting” (Rubin, 2023, p. 7).

On an episode of Debbie Millman’s podcast Design Matters, she interviews record executive and producer Rick Rubin and points to the above quotation from his 2023 book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being. Millman connects Rubin’s words to a story that author Elizabeth Gilbert tells in her 2009 TED Talk and 2016 book Big Magic. According to Gilbert, late American poet Ruth Stone said that while working in the field in rural Virginia, a poem would thunder over the land like a train, shaking the ground below her feet as it made its way toward her. Upon this thunder she would “run like hell” to the house for paper and pencil so that she could effectively catch the poem on the page. Unfortunately, there were times when Stone was not fast enough, and the poem would barrel through her and continue its journey looking for another poet who could bring it to life.

Rubin’s and Stone’s characterization of the ways ideas and art are not our own human manifestations, but rather individual, separate entities searching for a reliable maker to birth them into existence resonates with me. However, for most of my career in academia, I have been over-committed or working furiously to check items off my to-do list. At times, this frantic pace has allowed for my most creative ideas to be brought to life, but at others, I have been running so fast or for so long, that I can’t seem to effectively chase down the many ideas that come to me on a day-to-day basis. As Rubin and Stone suggest, with me out of breath, the ideas have been off to another maker.

Because of this incessant idea chasing and because being an artist is essential to my identity, purpose, and well-being in the academy (Willer, 2019), I have shifted away from imagining that ideas are something I must chase and catch. Rather, I imagine creativity as a companion I must “call in” or deliberately seek out, get to know through generous inquiry, and practice with love and devotion. Extending such affection has involved working diligently over the years to answer the question: how, in my work in academia, can I effectively call in ideas so that I can infuse creativity into my teaching, research, service, and leadership roles? In a world where students too are always on the move, how can I teach them to extend their hand to creativity to enrich their learning and lives?

These questions are particularly important for those of us from the arts to the sciences given that creativity includes producing unique and meaningful solutions, ideas, and products (Runco & Jaeger, 2012), hallmarks of our work in academia. Moreover, engaging in creative pursuits is associated with well-being, meaning and purpose, and character traits essential for academic and life-long thriving. For example, a meta-analysis of 26 studies points to the positive relationship between engaging in creative activities and well-being (specifically positive mood and affect) (Acar et al., 2020). Research also supports connections between creativity and finding meaning and purpose in work, life experiences, performing difficult tasks, and even mortality (see Kaufman, 2018 for a review). There are also links between creative behavior and empathy (Demetriou & Nicholl, 2022), as well as mathematical creativity and intellectual courage (Movshovitz-Hadar & Kleiner, 2009). In a study with college students, those who scored higher on creativity were more likely to value self-direction and openness to change and reject conformity and power values (Dollinger et al., 2007).

A myth regarding creative thinking is that it is uncontrollable and requires spontaneous inspiration (Benedek et al., 2021). However, research shows that creative cognition can be strategic and controllable (Benedek & Jauk, 2019; Silva, 2018). Additionally, a long line of research supports the notion that increased deliberate practice, including specialized training designed to improve certain performance areas, is predictive of performance level, even beyond experience or time spent in one’s field (Ericsson et al., 1993; Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996). What is more is that once base level knowledge and skills have been obtained, expert performers initiate creative pursuits, methods, and products (Ericsson et al., 1993; Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996). Perhaps then, we might consider that as we engage in deliberate creative practice and hone our skills in our research and teaching, the more creative we possibly become.

As such, working to develop opportunities to practice creativity is a meaningful and doable pursuit. Below I highlight three ways I have purposefully called creativity into my research and teaching over the years. I use recommendations from Rubin’s (2023) book The Creative Act: A Way of Being as framings for the stories and recommendations I share. Though Rubin’s above quotation suggests that ideas are out there and on to another maker unless we catch them, as the title of his book suggests, creativity also is a way of being that manifests through deliberate practice. Indeed, he notes that in practicing creativity we do not simply look for a signal “nor do we attempt to analyze our way into it. Instead we create open space that allows for it. A space so free of the normal overpacked condition of our minds that it functions as a vacuum. Drawing down the ideas that the universe is making available” (p. 8).

“Art is about the maker.

“Its aim: to be an expression of who we are.

“This makes competition absurd. Every artist’s playing field is specific to them. You are creating the work that best represents you. Another artist is making the work that best represents them. The two cannot be measured against one another” (Rubin, 2023, p. 237).

Several years ago, when my graduate students and I were leading an arts-based research collective for parents who had experienced the loss of a baby, I noticed that during our artmaking much of our time was being spent processing the unsupportive things friends and family members were saying to the parents in the face of their losses. They were struggling with friends who would try unsuccessfully to offer comfort with words such as, “at least you weren’t further along in your pregnancy” and brothers who rationalized that “God needed another angel.” After one of these workshops, an idea came barreling toward me: we should create greeting cards with compassionate messages that grieving parents actually find helpful!

I was overcome with creative inspiration; however, the daily demands of faculty life alongside mothering an infant and toddler slowed my ability to get moving on the idea. A month or so later, I finally started plotting out a plan, which included the students I would be teaching in the upcoming quarter doing a research project that would involve identifying patterns in what bereaved parents found compassionate following their loss. These messages would then serve as the foundation for our greeting cards.

Later, I was scrolling through social media, reveling in the brilliance of my idea, dreaming of how we likely would run Hallmark right out of business. But then my scrolling came to a halt when I came across a story about artist Emily McDowell who had to close down her website so that she could catch up on the onslaught of orders she was receiving for her Empathy Cards for those experiencing major illness, grief, or loss. Not only do the cards include beautifully whimsical artwork, but they say the most thoughtful, meaningful, and hilarious things. “How dare her!” I thought with envy. “She stole my idea!” But what I really was thinking was, “see, if only I had moved more quickly or if only I didn’t have all this other work to do and kids to take care of, that idea wouldn’t have been off looking for her.”

As Rubin’s above quotation suggests, after my initial disappointment, I reminded myself that my creative idea and Emily McDowell’s creative idea, while similar, were uniquely our own. Hers stemmed from her experience going through cancer treatment and her work as a professional artist. Mine was born from my experience with miscarriage and the death of my son, as well as my work as an amateur artist, researcher, and teacher. With this realization and humility, I called my idea back in and asked it if it still might be willing to allow me to bring it to life. My students and I carried out our compassion card project that led to the creation of our Live Out Loud Grieving Cards, which to date has been one of the most creative and meaningful ideas brought to light in my career (Willer, 2019). What I learned through this experience is that it’s ok to share overlapping ideas with other makers. We can teach our students that whereas we should certainly acknowledge and give credit to those who provide the inspiration that allows our own creativity to bloom, our ideas come alive when we feed them with our own unique stories, talents, and truths.

“Attuned choice by attuned choice, your entire life is a form of self-expression. You exist as a creative being in a creative universe. A singular work of art” (Rubin, 2023, p. 3).

“Good habits create good art. The way we do anything is the way we do everything. Treat each choice you make, each action you take, each word you speak with skillful care. The goal is to live your life in the service of art” (Rubin, 2023, p. 135).

For me, designing for a career and life of creativity has meant dressing the part. Indeed, dress is a practice that connects our bodies and identities (Entwistle, 2015). I have embraced fashion for as long as I can remember, an inclination passed down from my elegantly-dressed grandfather to my mom, who, despite not making a lot of money as a teacher, always saved enough to take me to Chicago twice a year to shop for special clothes no one else had. You will often find me on campus today in heart-patterned apparel, colorful cardigans, poofy shouldered tops, flowy skirts, patterned jumpsuits, and shoes precisely matching my outfit.

As I recently heard Tracee Ellis Ross say on an episode of the podcast We Can Do Hard Things, “it’s not look at me, it’s this is me” and fashion is “one of the ways I wear my insides on my outside.” Indeed, dressing in this way allows me to engage in an early morning creative act that sets the stage for a day filled with innovation and possibility. Wearing carefully crafted outfits make me feel like I am more open or identifiable to ideas looking for a maker in a sea of innovators, a way of signaling to them: “I’m right here!”

My late friend and former University of Denver colleague Dr. Christina Paguyo often wore brilliantly colorful jumpsuits to work. She loved Miuccia Prada’s quotation, “Fashion is instant language” (Burke, 2023). I like this too. People often comment on my clothes, which creates a momentary pause for connection we otherwise might not have shared. Additionally, dressing uniquely is a way for creative people to identify one another, leading to conversations that spark possible collaborations and idea generation. I can’t be sure, but it makes sense to me that when ideas come barreling toward us, calling them in as a team is easier than trying to do so alone.

Rubin (2023) notes that “practice is the embodiment of an approach to a concept” (p. 43) and suggests that if you want to be an artist, you have to be an artist. Dressing uniquely may not resonate or be affordable, or it may be precarious due to our own or students’ positionalities in the academy. But the deliberate practice of calling in ideas or embodying creativity can be as mundane or as extraordinary as we choose. “To create is to bring something into existence that wasn’t there before. It could be a conversation, the solution to a problem, a note to a friend, the rearrangement of furniture in a room, a new route home to avoid a traffic jam (Rubin, 2023, pp. 1-2). So, if we wish to be creative, our question—to ourselves and to our students—is “how do I wish to be and what calls me to create?”

“The experience of our inner world is often completely overlooked … Our inner world is every bit as interesting and beautiful, and surprising as nature itself. It is, after all, born of nature. When we go inside, we are processing what’s going on outside. We’re no longer separate. We’re connected. We are one” (Rubin, 2023, p. 60).

Though I often am dressed artfully, you also might catch me wearing my running or weightlifting clothes on campus. Given the hecticness of a typical day’s dropping off and picking kids from school, teaching, meetings, and writing, my schedule does not always allow me to fit my runs or strength sessions neatly in before or after coming to campus. Sometimes, heaven forbid, I go to the gym or run right smack in the middle of the workday.

In making these choices, I take the risk of being perceived as lacking “professionalism” or engaging in “time-wasting” not meant for work hours. I resist notions of what counts as “work” because there is research supporting the positive correlation between creativity and movement and fitness (Latorre Román, 2017; Rominger et al., 2020). I engage in weightlifting because “strength training has ‘lifted weight’ from my shoulders, my mind, my being. My embodied and emotional selves feel solid, centered” (Tillman-Healy, 2009, p. 109). I run because doing so allows me to think in brilliant metaphor to creatively make sense of my life’s pleasures and pains, which I then write about in my research (Willer, 2020; 2022).

Whereas running and strength training are the embodied practices that allow me to go inside myself in the name of creating, others might turn toward walking, meditating, gardening, or taking a nature bath on the bed of the forest floor. Moreover, I recognize my status as a tenured, full professor allows me the ability to shift my hours, a luxury not afforded to some faculty, staff, and students. They therefore may need to play with time during the work or school day to make space for turning inward in the name of creation. This might mean staff members rolling out the yoga mat in the office over a lunch break or faculty having students take a wellness stroll in one of the many DU gardens during a class period. In this way, we not only make space for ourselves to turn inward, but we acknowledge that calling in creativity is an integral part of our job deserving of precious work hours.

In Ruth Stone’s story about running like hell to catch her poems, she said that sometimes, she could feel the poem about to pass through her (Gilbert, 2009; 2016). In these moments she would grab a pencil in one hand just in time to transcribe. With the other hand she would reach out and grab the poem and pull it back into her body. In these moments of fury, she would transcribe the poem “page perfect and intact but backwards, from the last word to the first” (Gilbert, 2009). Perhaps what those of us in academia can learn from Stone is that whether we catch or call in our ideas, it is in the intentional practice—the repeated grabbing of the poem in Stone’s case, the on-going embodiment of creativity in mine—that we open the possibility for our ideas to be birthed in ways more magnificent than we could have ever imagined.

Erin K. Willer's Anti-Bio: I am the 4D Director of Faculty Innovation and a Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Denver. In my work as an artist/researcher/teacher/leader, I hold space for questions such as: How can we cultivate creativity, compassion, community, and well-being in the face of illness, death, and loss? How can art and other embodied practices allow us to resist oppressive structures in the name of moving toward/in freedom? How can we create academic spaces where students, staff, faculty, and administrators experience belonging, courage, trust, purpose, and love? I take great pride in my academic publications and the awards I’ve received for my research and teaching, but I am proudest of the ways that I have vulnerably shared my life’s greatest losses, and in so doing, inspired my students to do the same in their own scholarship and classrooms. My greatest failures in the academy include, over-committing myself to the point of burnout (several times) and stepping out of my own light out of fear of burning others. Though my work blurs the bounds between my professional and personal life, in my “free time” you can often find me in search of awe—running mountain trails, making art out of words and memories, and serving as a witness to the stories of those suffering the calamities of life—all in the name of answering my life’s call to question “are you alive?”